MASTERS OF MINIMALISM

Minimalism or minimalist art can be seen as extending the abstract idea that art should have its own reality and not be an imitation of some other thing. Minimalism narrows art to its essentials—material, measure, and perception—so that what counts is what is actually there. No attempt is made to represent an outside reality, the artist wants the viewer to respond only to what is in front of them. The medium (or material) from which it is made, and the form of the work is the reality. Minimalist painter Frank Stella famously said about his paintings ‘What you see is what you see’.This collection focuses on that discipline as it plays out primarily on paper, where process and structure read with particular clarity.

Minimalism emerged in America in the late 1950s when artists such as Frank Stella whose Black Paintings were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1959, began to turn away from the gestural art of the previous generation. It flourished in the 1960s and 1970s with Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Agnes Martin, Robert Ryman and Fred Sandback becoming important innovators.

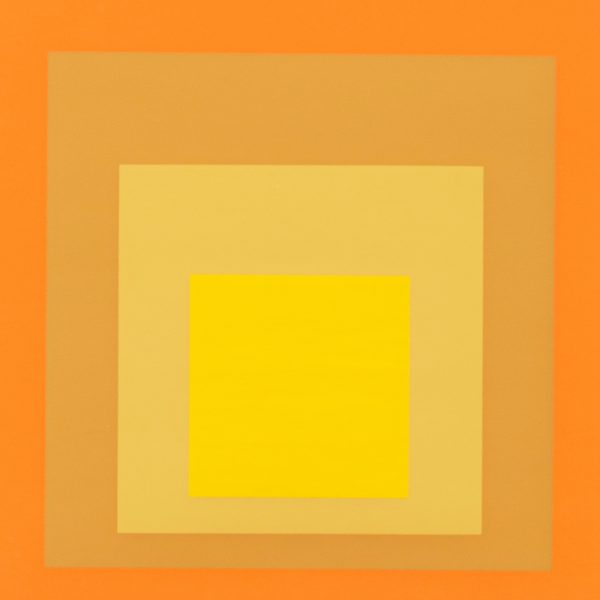

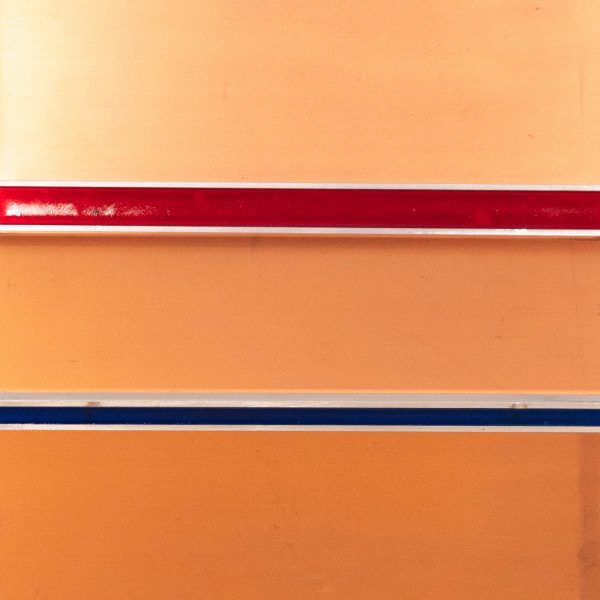

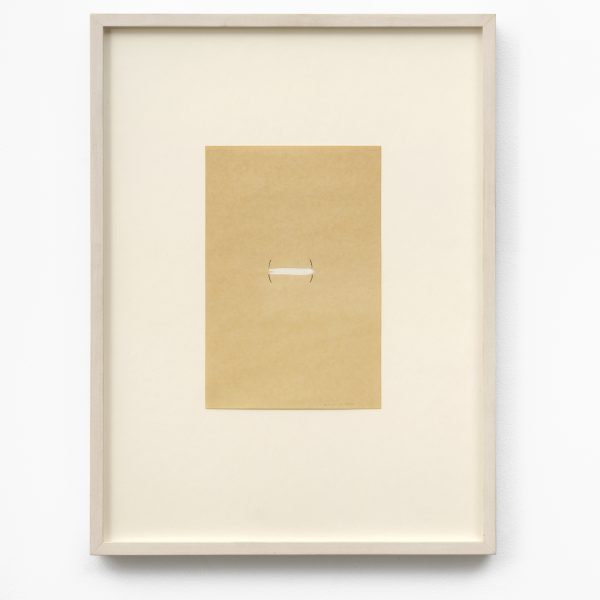

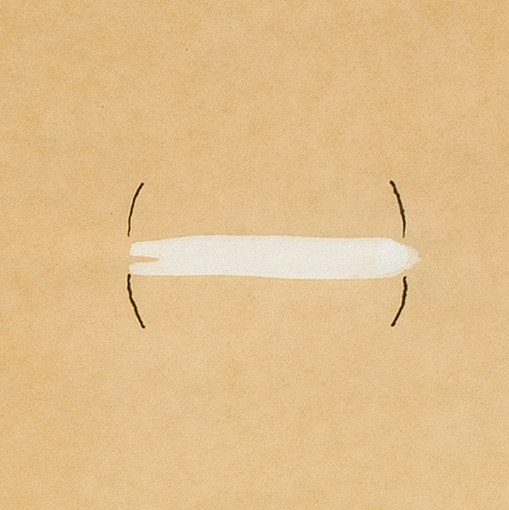

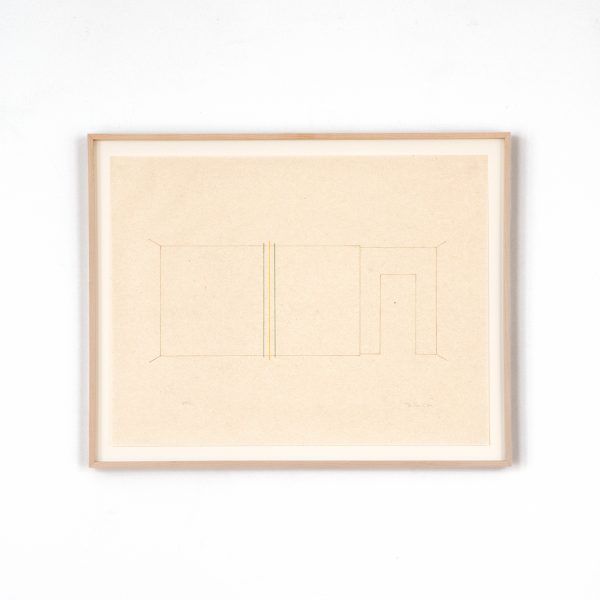

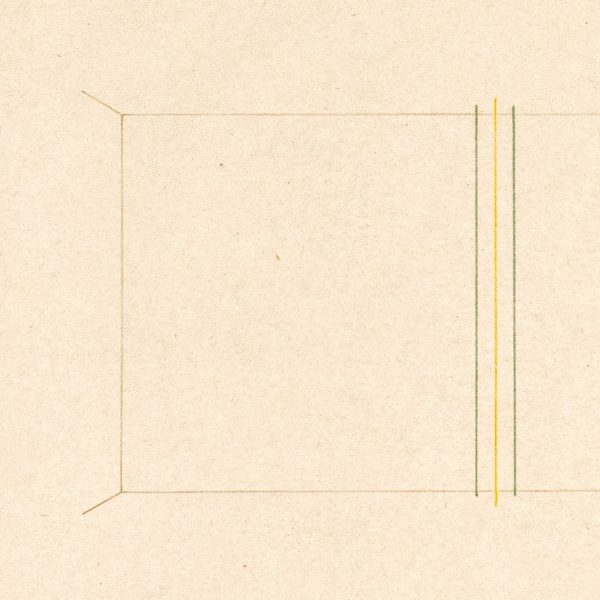

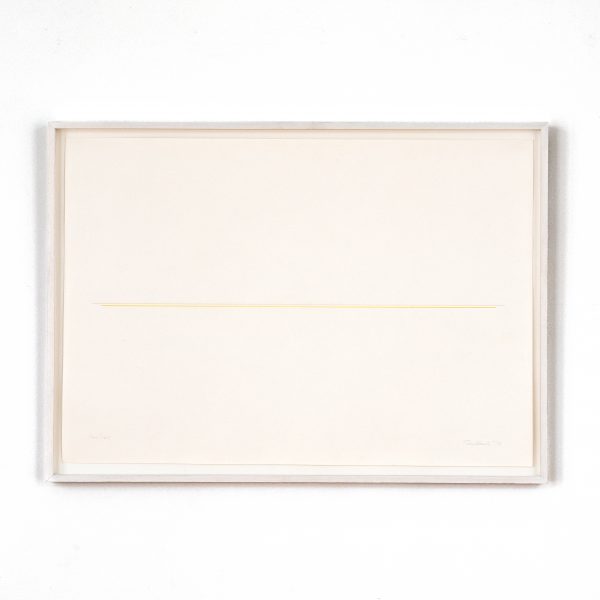

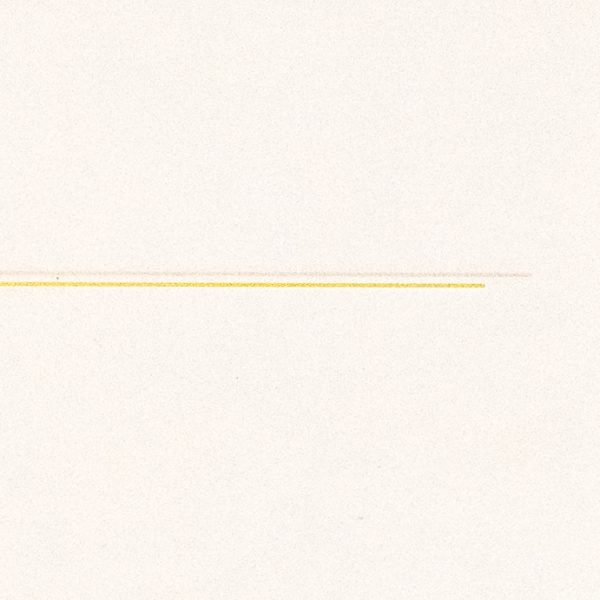

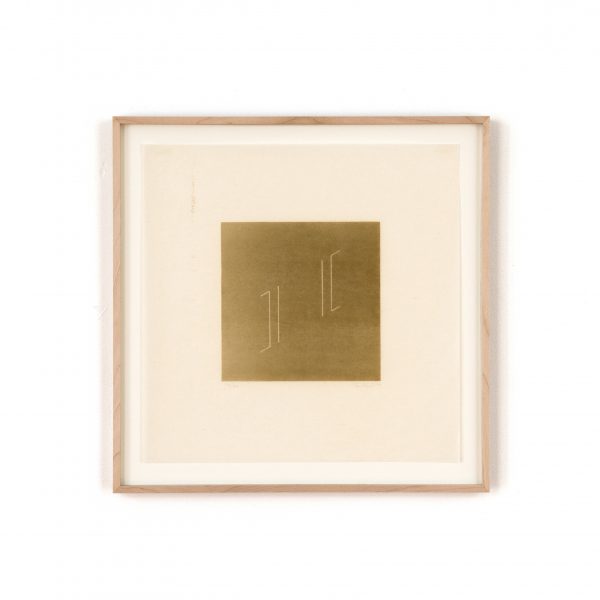

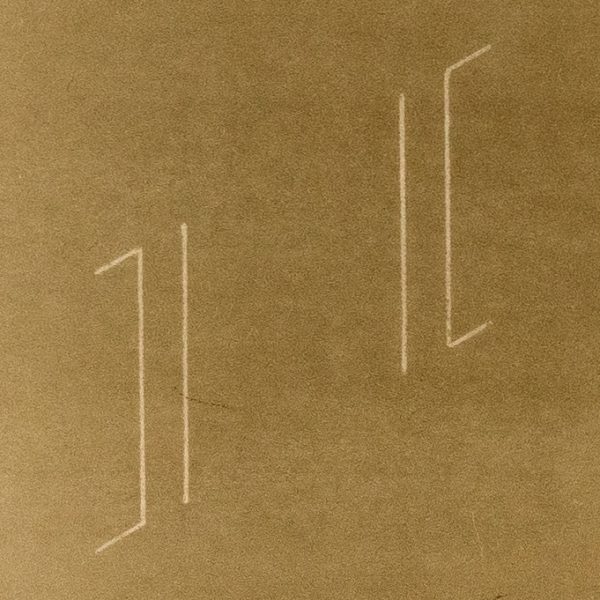

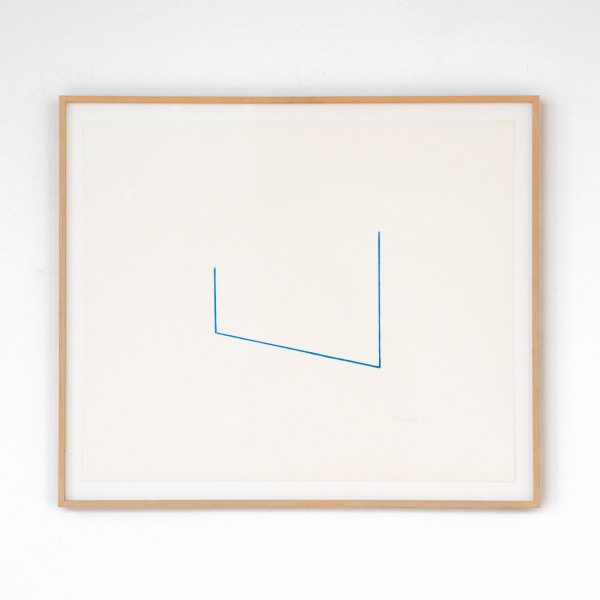

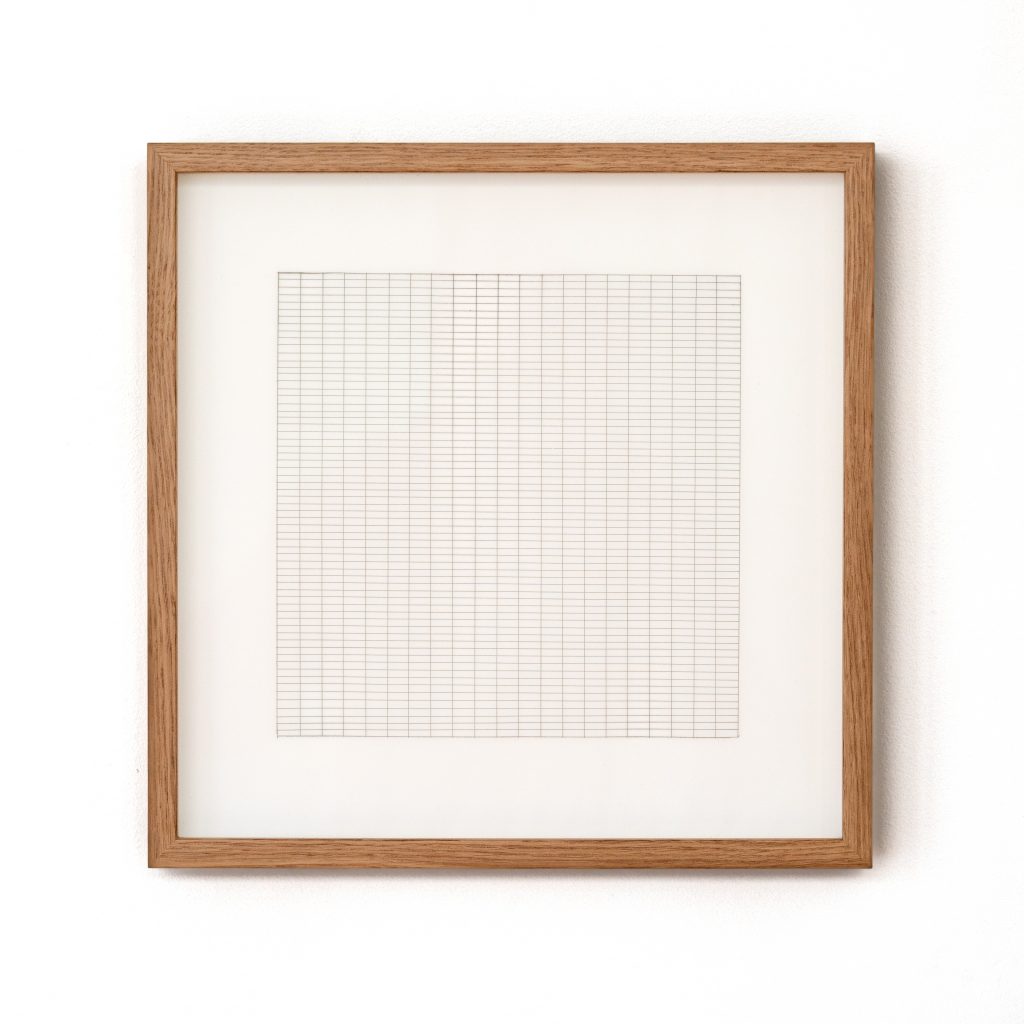

Agnes Martin’s restrained grids register as intervals of touch and time, proposing drawing and print as fields of attention rather than image. Robert Ryman treats the sheet as object: edge, fastener, stroke, and support become the subject, shifting “painting” into a set of material decisions. Fred Sandback translates his spatial “drawing” into planar terms; line and interval articulate volume without mass. Josef Albers—an essential precursor—uses the repeatable logic of print to demonstrate that color is relational and precise, its effect contingent on adjacency and scale. Richard Tuttle advances Minimalism at intimate scale: a spare drawing whose economy of mark turns looking itself into the event. Extending the conversation beyond paper, Keith Sonnier’s wall-mounted sculpture in copper and resin , emphasising contour, surface and structure, underscores the commitment to material presence.

Seen together, these works trace a concise history of reduction as invention: seriality, repetition, and the primacy of materials over depiction. The aim is not austerity for its own sake, but clarity—an art that resolves in the act of looking, where small shifts in surface, color, and proportion register with uncommon force.